(Turdus pilaris & Turdus iliacus)

Every winter our

fields, hedgerows and berry-bearing trees are inundated with ravenous visitors

from the north. The invasion of these so-called Winter Thrushes descends on us like a plague beginning

usually in mid-October but, dependant on weather conditions in Scandinavia and Russia, it’s sometimes earlier or

later than this.

The European

population of Fieldfare and Redwing that visit Britain are thought to be around

three quarters of a million of each species but we also see other members of

this family throughout our winter. Breeding populations of Song Thrush, Mistle Thrush and Blackbird tend to move southward to warmer climes but a good few hang on. Our resident Blackbird numbers are bolstered by European migrants escaping the severe winter

weather in their own breeding grounds.

The Fieldfare is just

a little smaller than a Mistle Thrush and easily identified, the red/brown back

is sandwiched between the battleship grey head and rump the contrast is clearly

visible. Redwings are similar

to Song Thrushes but the obvious buff stripes over the eyes and through the

moustache are striking in appearance and the main identification factor when

the bird is at rest or feeding. It is not until the bird is in flight that we

see from whence came the name, (redwing) then you will notice the red underwing

flashing like a red warning light as it rapidly flies away when disturbed.

European populations of Fieldfare and Redwing are thought to be in the region of 15 million breeding pairs for each species. Both species breed in many countries throughout the continent and have also been recorded as a rare breeding bird in

David Shallcross

Information from a variety of publications including L.O.S. Newsletters

Update from the British Trust for Ornithology web site.

Provisional results 2012/13 – a first look

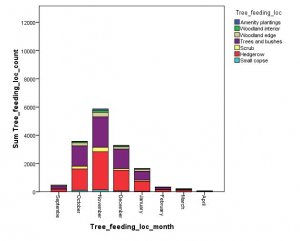

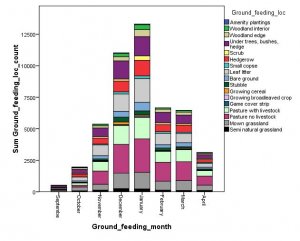

Data collection for the survey's second and final winter is already in full swing. Meanwhile, we already have some tantalising provisional results that show the kind of new science that is hidden in the first winter's data. The two charts to the right are by no means a final conclusion: indeed there is a long way to go to tease out the complexities that are summarised here and work out the conclusions that can reliably be drawn.

A major part of the analysis is likely to centre around the seasonal change from feeding in trees and bushes (Fig 1), which peaked in November, to feeding on the ground later in the winter (seen by comparing the timing of the peaks in Figs 1 & 2). This change was evident in all the thrush species and stems from their use of berries and fruits in hedgerows and trees until those supplies run low, followed by foraging on the ground, mainly for fallen fruit or for soil invertebrates. We are investigating how the timing of this change varies with species and region and your new data will show whether similar patterns will emerge in 2013/14.

Subdivisions of the bars on the histograms suggest rather little proportional change between feeding locations as winter progresses, other than between 'tree feeding' (Fig 1) and 'ground feeding' (Fig 2).

Observations on foods taken by thrushes during the first winter of WTS also show seasonal changes that may relate to the ripening of fruits and berries and their subsequent depletion. The massive scale of WTS observations will allow us to document the winter feeding behaviour of thrushes in far more detail than ever before. And results of the core surveys, on randomly selected sites, will help us differentiate between observer and thrush location preferences.

2 comments:

Great stuff David, that's got the ball rolling.

Thanks, Martyn

an update to the article courtesy of the B.T.O.

Post a Comment

Please type your comment into the box below, putting your name in the text. Then select 'Anonymous' in the 'Comment as:' drop down list and click the 'Publish' button to finish.